Who Watches The Watchmen?

The Marriage of Words & Pictures

With the critical and commercial success of V For Vendetta, the third of Alan Moore's works to be adapted to film, it is a matter of intense speculation as to whether his most acclaimed work will ever make it to the screen. Watchmen has been in print for twenty years, and Hollywood has been actively interested in the property for almost as long. Putting aside the issue of the professional conflicts that have been a barrier to its production, there is the fundamental question of its adaptability, problematic not least because of its length and complexity. Despite Hollywood's inclination to see comic books as stories ready-made with pictures to be turned into films, the graphic novel nee comic book medium incorporates storytelling devices unique to it, and Watchmen employs them to their very best effect. Comic books are a "unique form of communication that appeals simultaneously to both halves of the brain," according to Pedro Mota. The real question then, is whether Watchmen's incarnation as a graphic novel is not its ultimate manifestation. The greater public's failure to grasp the full potential of the sequential art form and its virtues may limit their ability to see that as a "comic book" Watchmen already achieves everything it could as a movie, and in fact, a good deal more. Comics, like cinema, are overwhelmingly considered to be a visual medium–by their readers, adherents and, above all, their producers. Too often, this emphasis on their visual component becomes a limitation; it inevitably draws a comparison to cinema that fails to recognize the textual component of comics as equally compelling. As a print medium, comics have their own tradition to draw on as well. Alan Moore emerged as one of the first writers in the form to have a recognized style. With Watchmen, Moore and Dave Gibbons made fuller use of the visual language of comics than had often been seen before, taking their cues from cinematic technique; but Moore also infused the text with a sophisticated literary style that is recognizably not of the cinema. Lastly, what made Watchmen so successful with its original audience, comic book fans, was the clever and original approach to generic conventions, namely superheroes, that are not only native to the form but are so closely associated with it that they will always seem less natural when presented in any other medium. Watchmen is celebrated not because it transcends the boundaries of its form, but because it explores and defines them so well.

The sophistication, adult themes and very dark worldview of Watchmen placed demands on the medium as few other works had before. To successfully meet this challenge, Moore, in close collaboration with artist Dave Gibbons, employed more complex visual storytelling techniques than was typical of the form, having forerunners in the work of Steranko, Eisner, and a few others.

During the course of the series we exlored most of the possibilities of the new forms of story-telling that we originated especially for Watchmen. So no, we didn't have any idea at the beginning. It was something which just emerged from the story as we were telling. it. The story seemed to demand a specific way in telling it, a specific way of seeing the world. It had to be seen all at once rather than in a strictly linear way.2

The simultaneity of experience Moore is describing is only possible through the use of images. A prose description of many details would necessarily involve a progression through them by the reader. Visual presentation can involve authorial choice, framing the picture in such a way that certain aspects are brought out more than others. Even when this is the case, the presentation can choose whether to limit the viewer's focus, or to allow full access to all the information that the image may contain. When filming, this would be deep focus, adjusting the camera settings to present all of the image with clarity, background as well as foreground, thereby permitting more details to be perceivable- the copy of Philip Wylie's Gladiator in Hollis Mason's apartment, the brand of perfume Laurie Juspekzyck is carrying around: "We were having massive amounts of background detail, but it wasn't sight gags; it was sight dramatics, if you like. And background details that worked in service of the story in the same way."3

Moore and Gibbons also built on the medium's established visual storytelling techniques. In any kind of storytelling involving images, still pictures are used to simulate movement, such as with flipbooks- small, usually lighthearted volumes of pictures that the viewer is expected to make use of by rapidly flipping the pages in order to view a series of images quickly enough to create the illusion of motion. This is equally true of films, which are, after all, really a series of still pictures shown at twenty-four frames per second, and comic books, which use illustrations in an ordered sequence to suggest the narrative’s progression through time and space. Images are never a true “imitation of life”; they exist in two dimensions and can only create the illusion of perpetual motion.

Comic books, the antecedent of the graphic novel and essentially the same in form, differing only in structure and content, are the midpoint between the purely descriptive (non-visual) narrative of literature and the wholly visual storytelling of film. They are akin to storyboards, graphic breakdowns of films made during pre-production, each drawing representing how a shot will look, collectively giving a sense of how the film will flow visually.

Storyboards and comics serve the same function- they are series of visual placeholders, representations of key visual elements of the narrative. Both are, in a sense, intrinsically incomplete: they are made up of selected moments in the story, leaving inherent gaps in their representation of the narrative. Comics, of course, bridge this gap with dialogue and narration; storyboards traditionally are not intended to be a fully comprehensive narrative, only an approximation of one, and therefore don’t have the same burden.

The necessary cooperation of words and pictures to tell a story is both comics’ greatest virtue and their greatest weakness. The reader must make the connection between two consecutive pictures and infer the time and space that bridges the space between them. Like the era of film which prohibited a gun being fired and a person being shot to occupy the same visual space, requiring the viewer to logically interpret the relationship between the first image shown and the subsequent result, comic books require readers to look at the sequence of pictures and recognize how each leads to the next. In the former case this was an issue of morality, but with comics it is the nature of the form, and part of its charm. Comics offer their reader the power of images, just as film does, but also invite the reader to interact with the text, as literature does, asking that the reader’s imagination extrapolate from the images provided to create flow. This type of interaction is closer to that of reader and text than it is to viewer and image; that is the great genius of the art form, to demand a unique kind of participation from its audience.

Unfortunately, a drawback to having the pictures and text share space on the page is that it can confuse the relationship between them. Readers can create an implied visual component in their own mind, but not a textual one, and text that actually corresponds to the visual elements not represented must itself be. So words that belong to the unseen events happening between panels (pictures) must inevitably accompany the images either immediately preceding or following the narrative space they belong to. This can create awkward situations, such as an image of a character jumping over a piece of furniture accompanied by a passage of text containing what seems like an awful lot of dialogue for someone to deliver while they are in mid-air.

Watchmen addresses this in a number of ways. There are many sequences throughout the story that employ no words, wherein the action is represented entirely by pictures. This is the ultimate aim and achievement of a sequential art narrative: to create a sense of movement with a series of still pictures. Watchmen further meets the challenge of accomplishing it without any recourse to explanatory text. The nature of these silent sequences range from dynamic action scenes to quieter scenes involving minute movements.

The action scenes, such as the assassination attempt on Adrian Veidt, are static shots of causes and effects: Veidt seizes an ashtray in one panel, in a subsequent one he is holding it over his head, his pose suggesting he has just swung it like a club, a trail of blood in the air indicating the arc it traveled, and the form of his assailant in the lower part of the picture- with a similar trail of blood indicating he is moving opposite the object from the point of impact- suggesting the blow that has just occurred but which we haven't actually witnessed.

In a film these would be jump cuts, unnatural movements from image to image without the accompanying representation of time passing to account for movements through physical space. Seen in a movie, this would be jarring, calling attention to the act of editing and thwarting the illusion of a sequential narrative. In comics, the necessity of the viewer's supplying the information that exists between panels is intrinsic to the form and not distracting. Indeed, the dramatic jump from action to result actually serves to create a flow that simulates movement effectively.

What's more, it adds weight and emphasis to these specific components of the action, more so than any technique of film editing could. In film details might be shown in close-up, or in a shot of longer duration to reinforce their importance, but here they are the only images shown, selected from among the many micro-moments of each scene to be pictured. In film there are twenty-four frames to represent every second, in comics there is at most one, and not every second is represented; they must be carefully chosen.

The judicious use of images is equally evident in the scenes that involve less dynamic motion. Laurie's exploration of Nite Owl's basement lair in Chapter VII communicates her movements simply by presenting images of her in different positions relative to her surroundings. The scarcity of text even becomes an element within the narrative when, relying on the visual information communicated by pictorial labels that are used instead of written ones on an equipment console, she mistakes a flame-thrower for a dashboard lighter with dramatic results.

She is at the mercy of wordless pictures once again when in the airless environment of Mars and trying to communicate her predicament to the oblivious Dr. Manhattan without recourse to words. This scene could have been rendered just as effectively in a work of prose had that been the story's medium, but with the visual communication available in the graphic novel, the author is able to place the reader into the environment of the story, in the sense that the reader receives and interprets the information in the same way and at the same time as does Dr. Manhattan.

Rorshach's investigations into crime scenes are also shown pictorially, each illustration devoted to a small, detailed action that allow the scenes to unfold at a measured pace appropriate to the cautious, methodical undertaking that is being portrayed. Each illustration in this scene serves the function of a crime scene photograph: it is a detail shot, a cinematic close-up, that reveals a specific detail. The graphic novel offers us a kind of picture puzzle, thematicaly-linked still pictures that tell a story.

The first of these scenes also does something very un-cinematic: it violates the axis of action. Rorshach's exploration of a wardrobe containing a hidden compartment is shown from every possible angle, including opposing ones. The inconsistent points of view are slightly confusing, despite a consistently applied light-source that helps to maintain the integrity of the physical space.

Lighting is also used as a temporal element. A flashing neon sign outside the bedroom window of Edgar Jacobi provides a steady rhythm to a monologue delivered by The Comedian; alternating light and dark panels illustrate the light blinking on and off at regular intervals throughout the speech, and similarly, in another scene, make it clear that Rorshach's foot, appearing in one panel but not the next, is advancing steadily on Jacobi's door. The viewer sees movement that isn't there by looking at an object that occupies a space and then viewing the space with the object absent. In this way both time and movement are portrayed on the page.

The most notable representation of motion in the work is the use of images to represent an aspect of movement never before present in comics, one of perspective. The first page contains seven frames, each successive one containing the same image as the first, but seen from an increasing distance (and thus containing more information), giving a gradually expanding perspective. This sequential relationship is unusual in comics; the movement it is representing is not happening within the frame but is that of the frame itself. The distance between the viewer and what is being viewed is increasing; paralleling the movement of the camera in film.

For the first time, the art form is representing its own presence, as cinema does when it draws attention to itself by noticeably exerting its power to control how and what the viewer is perceiving in the image. It is a singularly cinematic device- giving the viewers the sense of their own movement through the visual space by their changing perspective. The structure is repeated on the closing page of chapter one, utilizing a visual device to reinforce the dramatic structure.

The single, frozen images that make up a comic book are also used to represent time passing, in the same way that film editing is. In the fight scenes the movement from action to action is meant to create the idea of figures in motion, to disguise or distract from the visual information that occupies the (unseen) space between frames. In a more extreme use of this technique, we see much greater progressions between panels, from location to location so rapidly and directly that the cinematic equivalent might be a montage. We witness Edgar Jacobi walking along in the rain, then in the next shot he is at his front door, then instantly inside hanging up his coat, then in an upstairs kitchen. The still shots collapse time; there is a logical progression in the presentation of his movements, but a too radical advancement from one point to the next to seem like a natural navigation through a physical space. Rather than trying to make the time that is lost between images unnoticeable, as with the action sequences, these more significant jumps from place to place call attention to themselves, to make it clear that time has passed. Such cinematic techniques create an authorial presence; the readers can feel Moore’s hand guiding them through this landscape, are struck by his orchestration of elements, like Orson Welles’s in Citizen Kane.

Time is manipulated in way not possible with just prose alone. Flashbacks occur in a visual dimension: words belonging to one moment accompany pictures belonging to another. Two police detectives investigate the scene of a homicide in Chapter One, and one of them hypothesizes how the crime was committed. As his accounting of events is displayed textually, the graphics alternate between the present scene, where he and his partner are searching the dead man’s apartment, and the scene he is describing (and visualizing), which occurred earlier. His monologue continues across the page uninterrupted, appearing with the pictures of the space in which he is giving it and the flashbacks alike.

Certainly it is possible to present such a flashback through description in the narrative prose of a traditional novel. But to describe both the scene that is being talked about and the scene in which someone is talking about it would be clumsy at the very least. The graphic novel accomplishes what previously only cinema had: we see what is happening in one scene while at the same time reading about it being discussed in another. The auditory (or in this case textual) element of the scene is occurring from elsewhere in the diegesis. The words presented are not being produced by a source within the picture we are looking at. They are being superimposed over a scene that we are viewing, and we know that their source exists somewhere else.

There is much juxtapositioning of words and images throughout the text. An extremely confrontational interview with the character of Dr. Manhattan is intermingled with another scene in which his lover and another character are being mugged. The illustrations alternate- one-for-one- switching back and forth between the two scenes while the dialogue originating in Dr. Manhattan’s press conference continues uninterrupted throughout both sets of pictures. The words from the first scene provide ironic counterpoint to the life and death struggle being played out in the other scene. As the mugging scene climaxes, the dynamic is reversed and the dialogue of that scene begins to appear with the images of the press conference, which is continuing to deteriorate. This is another instance wherein the visual component of comic books circumvents the limitations of literature. Novels sometimes use descriptive imagery alternating with narrative to try and achieve the same effect, but the result generally seems more distracting than cohesive.

Transitions between scenes also frequently employ a technique of contrasting words and images. When a government agent gives Laurie Juspeczyk a dire warning of trouble ahead, his statement carries over onto the beginning of the next scene, in which Rorschach presents a newspaper to his associate bearing a headline that seems to confirm the veracity of what’s been said in the previous scene.

This technique rarely appears in film, but it approximates a slow dissolve, in which a scene’s after image suggests a connection with the next one. There is a similar visual technique used to make transitions in Watchmen as well, wherein a figure will appear in one setting, then appear next occupying the same pose and position within the panel but in the context of a different scene, the background and wardrobe connoting a different time and place: Dr. Manhattan is standing with his hand on his chin, a contemplative expression on his face as he looks down at the body of a woman Edward Blake has just murdered in Vietnam, next he is seen from the same angle looking down at Edward Blake's grave in New York at Blake's funeral. The figure is the same except the brief trunks he was wearing in the one scene have been replaced by a dark suit in the other. Nothing else in the two panels is the same, but apart from the wardrobe change, the appearance of one could have been cut and pasted into the other.

The visual language that is intrinsic to the style of Watchmen, and in fact to Moore's other work as well, communicates on a direct level not easily attainable through prose alone. A scene featuring two principal characters, Jon and Laurie, alone in a room until the unexpected appearance of a third presence would be awkward to describe in words. Laurie, eyes closed, feeling both Jon's hands upon her face, is startled to feel a third hand there, when she had thought they were alone (they still were; Jon had cloned himself). A description of the situation would be confusing for the reader- making clear the simultaneity of the sensations of touch Laurie feels that alarm her would be cumbersome at best- but seeing what she is experiencing when a third hand enters the picture instantly communicates the cause for her emotional reaction.

Visual gags too, which, like other forms of humor, depend upon precise timing, don't survive explanation, a necessary component of written work. This is illustrated in a scene depicting a newsvendor and the sidewalk prophet (actually Rorschach) who frequents his newsstand. After his usual cryptic, disturbing remarks, Rorschach exits the scene only to suddenly return, startling the vendor. A protracted detailing of the scene, necessary if not illustrated, would bleed the situation of the inherent humor that is appreciated almost reflexively by seeing it happen.

Rorschach's mask is one of the key visual elements of the text. Named for the famous psychiatric test involving ink-blots, Rorschach wears a mask that covers his face completely, his features replaced by amorphous black shapes that re-arrange themselves continually. The great success of this device is that the reader imagines a facial expression suggested by the shapes appropriate to what is happening in the story. Whether Gibbons made a conscious effort to tailor the effect to suit each individual scene is irrelevant: the whole point of the original design was to let the viewer see what he or she wanted to, in this case what viewers thought should be there. If Watchmen was a traditional novel and we were reading about the mask, the author would have to describe the shapes in terms of what they suggested to him, or what he wanted the readers to see in their design, rather than leaving it up to the viewers to see what they will.

Visual and print mediums each have elements that are difficult to translate to the other. The interior voice and omniscient narration that can be present in fiction are often omitted or altered when adapted to film; characters' unspoken thoughts and feelings can only be directly stated in a voiceover, a technique many filmmakers seem to avoid. It is an acknowledged conceit of the art form that its preferred language is pictures. Likewise, there are many occurrences in film that would not work in a novel, most often involving time. A picture has the potential to communicate something to us with an immediacy that a narrative description cannot hope to achieve.

Moore consciously favored visual story-telling in his script. He eschewed thought balloons and narrative captioning, traditional devices in comic books. They are two of the most significant stylistic advantages that comics have over film, providing viewer access to characters' thoughts and presenting direct communication from the author. Instead, Moore operated within the limitations of purely visual storytelling by not accessing characters' thoughts. There are however, interior monologues presented in first person narration by several characters, notably Rorschach in the form of his journal. When there are internal monologues present in films, this type is most often the source; the generic conventions of hard-boiled pulp fiction so often involved the hero or private eye's articulated point of view that films growing out of this style incorporated it, representing it as a voiceover narration. Blade Runner has received some criticism for pairing such a literary device with its otherwise singularly cinematic style. Moore favored the journalistic first person monologue as the form of interior communication most associated with cinematic adaptation over the even less often adapted styles of omniscient third-person monologue and naturalistic stream-of-consciousness thought. It is nevertheless a fundamentally literary style presented, in this case necessarily, in a literary form: as printed words, returning the stylistic device to its original form.

Comic books transcend literature's limitation of only description by representing auditory elements visually. As onomatopoeia use literal sounds as language to describe those sounds, lettering in cartooning and illustration suggests the type of sound it is representing by the way it suggests it visually. Large, imposing letterforms are commonly used to convey the impression of loud sounds; whispers are usually conveyed with exceptionally small fonts and perhaps accompanied by faint or broken lines. Sources of dialogue or other verbal elements are enclosed in bubbles or balloons that are superimposed over the artwork and attributed to their sources by directional pointers.

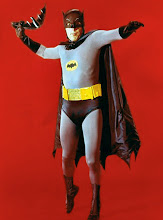

These too can be tailored to a specific effect. A plot detail involving the character Rorschach concerns his speech pattern, a droning monotone. Where in film such an element would be self-evident and in literature conveyed purely by description, comics' representation of such a phenomenon employs its own unique methods. As readers, we are first made aware of the unique character of Rorschach's dialogue by the other characters commenting on it, a more or less literary device. It is further alluded to in a manner one step closer to film, by having the actual text of Rorschach's speech presented in stylized dialogue balloons that noticeably differentiate his speech from that of the other characters. A key facet of Rorschach's character is his alienation; he is an outsider even among the rather exclusive group that form his peers. It's established that his speech took on its peculiar character after a traumatic event in the past. In flashbacks occurring before that event, Rorschach's dialogue is presented in conventional dialogue balloons lacking the stylized design that indicates the unusual manner of talking he has later. This subtle manner of reinforcing his character arc using a visual signifier is a very cinematic approach; what's more, Watchmen circumvents the lack of an audible dimension of its medium by representing sound in a visual manner not available to film, or at least not traditionally. The only comparable effect is the use of the brightly colored words delineating sound effects during the fight scenes in the film Batman (1966), in that case a comic book technique translated to film.

The many sequences that present purely visual storytelling are balanced by instances where printed words dominate the page. The penultimate chapter, set at an Antarctic retreat, begins with a series of images that are mostly obscured by solid whiteness (as was the cover for the original issue as well), meant to convey the weather conditions. The most prominent element in these panels are the dialogue balloons containing Adrian Veidt's speech, a monologue discussing his practice of watching dozens of television sets simultaneously to obtain a massive information feed and analyze patterns in mass-distributed imagery. When he is first depicted engaged in this activity, the pictures on the televisions are presented without any representation of accompanying sounds; it is the images alone that either Veidt, or Moore and Gibbons, are concerned with. In the climax, however, Veidt turns the attention of the other cast members to the TVs so that they hear the information that is being relayed. Then the print conveying the audio of the sets dominates once again. It is the words, not the pictures, that are crucial to the denouement.

Moore began his career in comics as an illustrator, but has become known principally for his writing. Given his background as a visual artist, it's not surprising that he employs cinematic devices in his work. Nevertheless, he draws equally on the tradition of the printed word, and never completely abandons its precepts. In fact, he takes pains to represent it in a medium that doesn't favor text elements. Each of the chapters is supplemented by a text piece, meant to be a representation of an actual artifact from the story itself, reproduced in the format of the original; book excerpts, newspaper and magazine articles, memos, even hand-written notes- all of these are rendered as closely to what they are modeled on as possible. Moore evidently feels that there is another level of communication possible to convey by presenting information in the context we might encounter it outside the narrative, he furthers the illusion of the reality of the story. The opening chapters of Hollis Mason's book, which immediately follow the opening chapters of Watchmen, speak directly to the goal of using the printed word as a way of telling a story, and here Moore speaks eloquently of the challenge of affecting an audience through the power of words alone, and by doing so, meets that challenge.

He further provides evidence of his love the literary tradition in sequences that are meant to be taken from a comic book being read by one of the minor characters in the larger story. The action of "Tales of the Black Freighter" thematically parallels that of Watchmen, and like the text pieces, it is a more literal representation of an element of the story. It is a comic book, representing a comic book within the story, whereas the people, locations and events in Watchmen are only a comic book representing them. The tale is set in colonial times, and the narrative captions are both in the language and of the appearance of prose works of that day. The captions are made to look written is script; even the framing boxes are style to look like curling parchment paper. If Moore, working in the late twentieth century, is unavoidably influenced by the style of cinema, he evinces a love of much older stylistic traditions and demonstrates his affection for them.

The story of the Black Freighter, while evincing a motif that reflects the literary period of the story's setting, is actually a tribute to a more recent tradition: that of comic books. The comic book story is told in the style of the E. C. comics of the 1950s, and the text piece following the chapter featuring one of the tale's installments is a fictionalized history of events relating to the comic industry. The re-imagining of real events is grounded in the central premise of the book: how superheroes would be perceived, operate in, and affect the real world. Moore takes this most prominent generic component of the medium and explores it in a way never done to this degree before. Watchmen is about a lot of things, but fundamental to its structure is the fact that it is a comic book about comic books, and no other medium could capture the significance it has for its own.

Terry Gilliam, erstwhile director of the proposed Watchmen film, recognizes the strengths of the work's original medium, and the difficulties in translating it into another:

Certain works should be left alone... in their original form. Everything does not have to become a movie. Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy was always best in its original manifestation... a radio show. So forget about the movies. Let your imagination animate the characters. Do your own sound effects. Your own camera moves. Dave Gibbons artwork is perfect. From my first reading of Watchmen, it felt like a movie. Why does it have to be a movie? Think of what will have to be lost. Is it worth it? 1

Like many successful writers of comics, Moore's artist background is key to his ability to tell stories with pictures, but he demonstrates a strong literary influence as well. He never sacrifices one storytelling method to the other, and by taking full advantage of both, realizes the potential of the medium. Watchmen is more than a film on paper; it has many of the virtues that can be found in film, but many that can't. It's ready-made for the cinema, a novel that is crafted around images, but a film-version could never equal the accomplishment of the original form, the perfect marriage of words and pictures.

1 Alan Moore: Portrait of an Extraordinary Gentleman, Smoky Man and Gary Spencer Millidge, Eds. (Abiogenesis Press, 2003) p.34

2(Alan Moore, The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore, Ed. George Khoury, Raleigh,NC, Two Morrows Publishing, 2003) p.111.

3 ibid, p.110

4 Terry Gilliam, from his introduction, Alan Moore: Portrait of an Extraordinary Gentleman, Smoky Man and Gary Spencer Millidge, Eds. (Abiogenesis Press, 2003) p.9

Friday, March 14, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment