The recent rash of comic book themed movies, Road to Perdition, Hellboy, Ghost World, Hulk, The Punisher, Constantine, Sin City, The Incredibles, et. al., has made clearer than ever:

the relationship between the comics and the cinema, two visual methods of storytelling which developed simultaneously and had a profound effect on each other, not only by providing source material, but also by suggesting to each other new methods of composition and new techniques for visual progression. 1

There is another, unexpected area of mutual influence the two are experiencing: their target audiences. As more and more comic book characters and storylines are adapted into motion pictures, they are being reinterpreted to fit the expectations of the larger audience associated with the latter medium. The heroes that once tried to appeal to an individual reader now must please a collective audience. The text therefore can no longer try to communicate with the reader/viewer as an individual, but instead with someone who is part of a group. This calls for a protagonist who is traditionally popular rather than singularly special.

1978’s Superman: The Movie was a faithful adaptation of the classic comic book mythos. The casting of an unknown actor (Christopher Reeve) in the title role preserved an essential component of that mythos: it allowed any potential viewer to identify with the character. This had been key to Superman’s success and longevity, that any man could see himself as both the unremarkable and oft times overlooked Clark Kent and the ideal that Superman represented, our collective potential realized.

Such a dual persona was a key factor in the success of adventure heroes that preceded Superman as well: The Lone Ranger, The Shadow, Zorro. But with Superman, it was even more crucial. Superman’s achievements were so far beyond the accomplishments of ordinary people, it was important not to establish him as complete unto himself, an identity that was completely unattainable, but instead to connect him with a character that was much more familiar, even someone the reader could become, a mild-mannered reporter, for instance. In fact, the longer Superman continued, in comic books, films, and various other media, the humbler, less respected, and generally undignified Clark Kent became. This made it easier for any reader/viewer to decide that if someone as bumbling as Clark could secretly be capable of such greatness, certainly so could the rest of us.

In the film version, a young Clark Kent is an outcast, ridiculed by his teenage peers. He is the water boy for his high school’s football team rather than a player. They taunt him and play cruel pranks at his expense. Clark is completely unsuccessful in his attempts at romance. He has no more luck with Lana Lang, a pretty cheerleader, than he will with Lois Lane, the object of his affections later in the film. Of course, as Superman, the situation is quite different. He commands respect, is sexually attractive and accomplishes his goals. He is the recourse that Clark has, and that anyone who is in Clark’s situation in real life can dream that they, too, can somehow manage to find in themselves.

The situation continues throughout the series of films. By Superman III (1983), nothing has changed. An adult Clark returns to his hometown of Smallville to be bullied once again by the former quarterback. He manages his revenge thanks to his secret powers, but always covertly. It’s OK for Clark’s secret to let him win out in the end; that’s the whole point. But his victory can never be as Clark. The audience needs to see the Superman fantasy always contrasted with Clark Kent’s reality- their reality. If Clark does all the things they dream of doing, it would just underscore that they can’t, because it would be clear that they were never really anything like Clark.

The formula worked well enough that it was often repeated. Superman’s chief sales rival in the 1940s was Captain Marvel, who shared so many of his attributes that it caused a lawsuit between their respective publishers. When it came to alter egos, Captain Marvel went Superman one better; whereas Clark Kent was an ordinary working man that the intended readership of young boys could relate to the average guy, Billy Batson was just a kid, someone the young reader could relate to himself.

Captain Marvel was the wish fulfillment of all young boys, to be able to outdo adults. This element of the character was maintained when translated into other mediums, a popular movie serial in the 1940’s, and a Saturday morning television show in the 1970s. The idea of being able to overcome one’s apparent limitations was especially inherent in the latter. Billy (played by Michael Gray) could perform heroic deeds, flouting the expectations of many of the people around him. Like Clark, Billy never got any of the credit for his alter ego’s deeds, and also like Clark, he was an orphan and an outsider, his true greatness recognized by no one.

Captain Marvel’s legal problems notwithstanding, another reason the character is today nowhere near as prominent as Superman, may be his alter ego’s identification with children. Clark’s awkwardness, his hard-nosed boss, Perry White, his elusive love interest, Lois Lane, made him easy for adults to relate to, and so his appeal was universal. Children will readily relate adult problems to their own, since it gives them a feeling that their own experiences are equally important. Billy, on the other hand, represented only the frustrations of childhood, something the audience would leave behind as they got older.

The dynamic of idealized fantasies incorporated in flawed characters was taken to the next level with Marvel Comics in the early 60s. Some of them retained the practice of having two identities, but more commonly the two were smashed into one, all-too recognizably human beings who acted out our most spectacular fantasies. Characters like The Fantastic Four had no secret identities. Their amazing natures were apparent to all, as were their many flaws; they were argumentative, nerdy, in some cases even ugly.

Spiderman and Daredevil were in the masked man tradition, their ordinary, almost pathetic selves not alluding to their wondrous other lives. Spiderman’s alias, Peter Parker, is cast very much in the Clark Kent mode: a nerdy outcast who is rejected by girls. Daredevil starts out in this vein, a bookworm named Matt Murdock who is picked on by the neighborhood toughs, but after Matt is blinded, he is even more of an outcast, respected, but pitied even more.

The angst and neurosis constantly on display in the Marvel Comics produced storytelling with a level of complexity and sophistication that made them popular with the college crowd, and their creator, Stan Lee, toured the University lecture circuit into the 1970s. Since that time, there has been a cultural shift on many levels. The repressive political atmosphere and cultural conformity of the Reagan era made it fashionable to be an outcast, at least in the world of the arts. Social outsiders like Cyndi Lauper and Billy Idol were popular entertainment figures because they championed the misfit. Super heroes began to flounder in this atmosphere, unsure where to stand, and Batman and Superman, once champions of the oppressed, began to be reinvented as voices of the establishment.

The influx of historically un-represented voices into the social dialogue, particularly in the form of hip-hop culture, Latin music and Asian film, readjusted the notion of who is an outsider within the cultural landscape. Today, being an “outsider” means being part of a collective identity, one that is laid claim to by various groups, not one that can be adopted by just anyone who doesn’t fit in with the dominant culture. Outsiders are no longer individuals, but specific groups that not just anyone can belong to.

There has also been an explosive expansion of youth culture. Popularity with an ever-renewing young audience is the decisive factor in determining how and what is marketed in almost every facet of commerce, but particularly in popular culture and entertainment.

Comic books and the other forms of entertainment they inspire today are slavishly faithful to this market. Where comic books were once aimed at a fairly specific, limited audience, they are now treated as merely an adjunct, to be used to develop product for the larger markets of toys, video games, and, most especially, motion pictures (85% of Marvel Entertainment’s profits come from video games, toys, and other licensing).

The end result is stories that reflect this social paradigm. Protagonists can no longer be misfits, isolated iconoclasts rebelling against the status quo. They must be crowd pleasers; the majority audience doesn’t want to relate to a loser, regardless of his hidden virtues. The skinny guy who gets sand kicked in his face at the beach deserves it as far as they’re concerned, and they don’t really want to hear anymore about it.

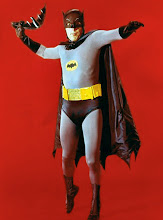

Super-heroes have been reinvented to please this audience. The Batman series of films reflects this change. There was much controversy over the casting of Michael Keaton in the title role for Batman (1989). He was short, not athletic and had a receding hairline. The producers felt the depth of character he could bring to the part was more important than classic good looks, and he returned again for the sequel, Batman Returns (1992). Keaton’s bespectacled, almost nerdy Bruce Wayne played into the classic tradition of having the hero’s bland exterior contrast with his more impressive hidden side.

By the fourth film, Batman and Robin (1997), sex appeal won out over character. The filmmakers cast George Clooney, People magazine’s sexiest man of the year, as Batman. The film ignored the character’s established neuroses, and emphasized group dynamics, focusing on his good-looking young sidekicks, Robin and Batgirl. The latter was played by Alicia Silverstone, a teen idol, and was transformed from her previous incarnation as head librarian to a college bad girl.

Spiderman (2002) remains fairly true to its source material; Peter Parker in the film is a genuine nerd, although star Tobey Maguire was required to weight-train, bulking up to play the superhero. Ironically, despite adding at least forty pounds of lean muscle mass, Maguire was described as being deficient as an action star in the press, considered “not hunky enough.” It is very clear that in cinematic terms, looking heroic means looking like a movie star. The new audience for superheroes wants perfection, not imperfection.

Daredevil (2003) featuring Ben Afleck as Matt Murdock, adapted itself better to suit the demands of its audience. Afleck’s interpretation was a far cry from the introspective, studious character of the comic book. In fact, Afleck himself projects a persona that is light years away from the original concept. His overwhelming popularity in real life creates an air of entitlement that he carries with him no matter what role he plays. He is an outgoing, confident jock, nothing like the quiet, thoughtful hero of the comic.

His best friend, Franklin “Foggy” Nelson is played by Jon Favereau, best known for male-bonding pictures like Swingers. In the comics, Foggy is a weak-willed, needy, whiny, fat guy, whom Matt knew and befriended in college. Foggy was snubbed by his more popular classmates, his one friend a blind man that everyone else pitied or just ignored.

The film has Matt and Foggy as a couple of regular guys, boisterously joking around in a coffee shop, just before Matt picks up Elektra, his future love interest. They are so traditionally masculine, it’s hard to imagine either of them ever having a hard time being accepted by their peers. Although the dialogue in the scene between Matt and Elektra is lifted intact from the comic book, the understated charm that Matt uses to win Elektra on the page is replaced by Afleck’s cocky self-confidence.

The film wants to present Matt as being like Afleck, a popular, winning, Guy-Most- Likely-To type. This will then make him appeal to guys like Afleck, and to the majority who would like to be like them, rather than like the guys they beat up. Presumably only viewers who see themselves as outsiders want to watch a movie built around one, and they apparently don’t make up a large enough market share to satisfy the filmmakers.

Even more concerned with being popular with the in-crowd is the latest live-action interpretation of Superman. Television’s Smallville, appearing on the WB network, is concerned with the teenage years of a young Clark Kent. He’s a far cry from the boy that appeared in the earlier film. Instead of the water boy, Clark is the star of his high school football team. He doesn’t hide behind a pair of glasses, and the girl trouble he has is more along the lines of having more girlfriends than he knows what to do with, including the prized Lana Lang, the gorgeous cheerleader who had once proved so elusive.

This Clark is a super-hunk, played by Tom Welling. His attractiveness is emphasized and reflected by his fellow cast members, all young and exceptionally attractive, standard method of operating at WB. One scene in the first season had Welling and Sam Jones, who plays Clark’s best friend Pete Ross, appear shirtless during a doctor’s visit. The two actors practically tripped over one another, crowding each other out of the frame while jostling for a position to better show off their impressive physiques.

Even Clark’s parents, traditionally portrayed as an elderly couple who adopt him when they are past child-bearing age, are younger and better-looking, played with genuine sexual chemistry by the handsomely middle-aged Annette O’Tool, and John Schneider, himself an established television sex symbol of another era.

It’s almost impossible to imagine Smallville’s Clark Kent ever actually becoming the more famous version of Superman; it’s too far removed from the lifestyle of the people he’s meant to appeal to. This incarnation of Superman reflects the priorities of its chosen audience.

The Fantastic Four movies follow in the direction of youthful sex appeal. The originally demure Susan Storm is played by the sensuous Jessica Alba, who would look more at home as a pin-up in some jock’s locker than she ever would have in the pages of some four-eyed nerd’s comic book.

Comic book heroes no longer belong to the nerdy kids who got picked on for reading them. Today’s superheroes belong to a new generation, one that is more concerned with appearances. Superheroes have been translated into movie stars, with all of the attendant superficiality and shallowness.

“I believe there’s a hero in all of us,” Aunt May tells Peter Parker in the second Spiderman film, but for the mass audience, a hero is somebody that everybody likes, a winner. They want to see themselves as that person, and they’re not interested in seeing themselves as a loser.

1 Les Daniels, Comix: A History of Comic Books in America, (New York, Bonanza Books, 1972), p.10

Tuesday, March 11, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment