With the long--but perhaps little--awaited release of the 2002-2003 series

Birds of Prey on DVD, it's worthwhile to examine why the television show was so short-lived, while the comic series it's based on has proved to be one of the longest-running mainstream comic books centered around female characters in the last forty years.

The question of why the show didn't succeed whereas the comic has flourished has a similar answer to a related question: where did BoP go wrong when trying to duplicate the success of its predecessor, Smallville, an unqualified hit? Smallville was the WB Network's attempt to adapt DC Comic's familiar icon, Superman, for its primary audience of teens by concentrating on elements of his mythos related to the character's adolescence. When the show proved popular, they attempted to do it again with a property that would target a female audience, typically a minority one for action or adventure-themed entertainment, especially when it involves comic book superheroes. Tailoring a story about superheroes for teenagers is like developing a canned tuna fish that appeals to cats, but getting girls to look at people in capes hitting each other is an entirely different kind of challenge. Smallville was aimed at the same audience that comic books always have been; Birds of Prey was trying to conquer new territory.

Essentially, this had been the same challenge faced by the comic series, although the publishers were probably more concerned with appealing to their overwhelmingly male audience, one that had traditionally shown less interest in female protagonists. That trend had been considerably reversed in recent years by some artists' emphasis on female anatomy and revealing costumes, and certainly BoP did try to exploit male readers' interest in attractive women, but it also seemed to make an effort to tell stories that reflected the priorities and interests of women that differed from those of men.

First and foremost among these was female friendship. The two principal characters, Dinah Lance, a. k. a. Black Canary, and Barbara Gordon, alias Oracle, establish a close friendship over the course of the series, effectively becoming gal-pals. The need for a gender peer to relate to is something that male heroes rarely evince except for the sidekick phenomenon, which had long proved problematic. As her field agent, Black Canary remained in constant radio contact with Oracle, effecting a situation wherein they would engage in a dialogue that carried over an entire issue. In this way, the structure of the narrative facilitated characterization for female--and male--readers who recognized the general truism that it demonstrated: women like to talk to each other.

Probably this was why the series was chosen to be adapted. The network thought that the same dynamic of female friendships that had been key to the success of shows like Sex and the City and their own Gilmore Girls could be superimposed onto an action/adventure show. Likewise, they tried to blend story elements like dating or a character's interest in fashion with the generic elements of a show about superheroes in a misguided attempt to convince young women that this was a show about people just like themselves, that the fact that they had superpowers and formidable hand-to-hand combat skills was merely incidental.

This proved to be a mistake. Having Huntress, who had replaced Black Canary as the lead character in the TV version, bicker with Dinah over clothes or the two tease one another about their respective romantic interests tended to trivialize the more serious parts of the story. The attempt to humanize the characters by giving them familiar concerns injected a sense of banality into the show that robbed it of dramatic impact. The show's creators tried too hard to craft a super-hero show that was what they perceived women to be interested in, which unfortunately was not super-heroes. The women's sometimes blithe attitude towards the comic-book conventions that were part of the story, including their own superpowers, made those elements seem silly. Having the characters be fashion-conscious and focused on interpersonal relationships need not have been at odds with action or science-fiction plots, but when wardrobe is give equal weight to life and death situations, it undercuts believability.

The comic book has also sometimes made an ill-considered effort at being female-friendly; an early story arc centered on Black Canary's romantic misadventure with a con man who has also seduced guest stars Catwoman and The Huntress (who became a regular member of the cast after the inception of the television program) in turn. The dating lives of Dinah, Barbara, and later, Helena (Huntress), have been recurring concerns in the comic series, but, key to its success, have never eclipsed the central relationship, the partnership of Dinah and Barbara.

The television version erred in introducing a male lead, whereas the comic has no regularly-appearing male characters. Shemar Moore's Jesse Reese is a love interest for Huntress and eye-candy for the viewers, an almost unavoidable concession to the producers' idea of the audience's expectations. The comic book avoids using male sexual attractiveness, for the wrong reason, but to the best effect: the heterosexual male perspective is too well-entrenched in mainstream comic books to allow men to be used as sex objects for marketing purposes, which probably helped the series flourish by not alienating the largely male audience. Happily, it simultaneously produces another result: the story is able to focus on the inner lives, priorities, and perspectives of the heroines without any competing male protagonists to pull focus. Male superheroes may have female love interests, but Superman never had to worry about Lois horning in on the action.

The central reason Birds of Prey did not succeed, was probably its break with the established continuity of the DC comic book, especially as the show drew on the tightly-interconnected Batman family of books, whose hardcore fans are notoriously unforgiving of even the smallest inconsistencies. Smallville also departed from the Superman backstory, but less so at the outset, and only significantly after the show had built up momentum and an audience.

Ironically, BoP was in many ways more faithful to established continuity than its predecessor, since it married irreconcilable elements from conflicting historical and contemporary versions of the characters. Referencing the meta-gene that had been used throughout DC's line as a plot device, the TV show gave Huntress super-human abilities neither she nor Catwoman had ever displayed in the comics, but consistent with the suggestion of supernatural powers Catwoman displayed in Batman Returns. Huntress seems to be the daughter of that Catwoman, shown sporting the same costume and hair color familiar to moviegoers, unsurprisingly, since the show was trying to reach the same mass audience. As Paul Levitz points out in an introduction written for the DVD, The Huntress, as originally created, was the adult daughter of Batman and Catwoman (although not illegitimate, as on the show).

However, the character was a product of DC's penchant for parallel universes, which facilitated the existence of such an impossible character, since the ongoing Batman storyline portrayed Batman as roughly 30 years old, and his feelings for Catwoman largely unresolved. She appeared irregularly, but proved popular enough to merit rewriting the character's origin after DC's seminal Crisis On Infinite Earths series eliminated multiple versions of their characters, necessitating Huntress's reinvention as Batman's peer, with no relationship to Catwoman.

A similar chain of circumstances led to Black Canary becoming her own daughter, or more simply, being established as having inherited her costumed identity from her mother, once the character had been around long enough to raise questions about her age. The television show maintains the generational aspect of the role, but the super-powered martial artist and daughter of the original known to longtime fans of the character is not the Dinah Lance that appears in the show. Rather, the Black Canary known to comic book readers is the mother in this pair, making only a single appearance, and the very unfamiliar Dinah Lance that appears regularly on the series is still in her teens. The writers have given her psychic powers, perhaps to soften the tone of the show, ESP presumably being more feminine--or at least less threatening--than a black belt in karate.

This was the show's biggest misstep. The girlish, sometimes mousy Dinah that is offered to female viewers as relatable is a far cry from the star of the comic book, a fiercely independent, supremely capable woman approaching middle age yet still exploring her own identity (Note: By the start of the comic book series, it had been established in other titles that Black Canary was at least in her mid-thirties, but a subsequent immersion in the Lazarus Pit partially reversed the aging process), and after a long history in the DC universe at large, finally getting the spotlight. In trying to make her more relatable, the producers made her less effective and less interesting.

The character to most successfully transition from page to screen is Dina Meyer's well-realized Barbara Gordon. In flashbacks, she proves to be the most effective embodiment of the classic Batgirl character to date, but it's her portrayal of the more mature Barbara, having forged an entirely new identity for herself in the wake of tragedy as Oracle, that provides the heart of the show. The character bridges the current storylines in the comics, which she participates in, with that of the original Huntress, who was motivated to take up her father's mantle after her mother's murder, the two divergent tales revised to stem from a common set of events.

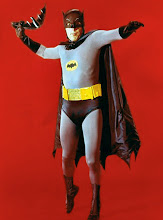

Birds of Prey, like Smallville, may have tried to pretend it wasn't a live-action comic book--the characters didn't wear capes or cowls--but it had less room to do so: Smallville is about a pre-Superman Clark Kent and could get away with never even referring to the icon by name; Birds of Prey was about a post-Batman group of heroines and could never deny its comic book roots. Comic book readers may not have embraced the show due to its divergence from the source material, but for some fans there are a lot of elements that can be recognized and appreciated. If the show is not entirely consistent with its comic book inspiration, it is at least true to it.

Saturday, March 28, 2009

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)